Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Aug-29-2010 15:25

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

Reframing the Environment (1)

Daniel Johnson Salem-News.comThe global environment is under assault as never before in history. But on this, America is off the hook; the United States is as much a victim of the environmental degradation as any other developed nation on earth.

Image courtesy of Roberto Rizzato |

(CALGARY, Alberta) - During the summer heat wave of 2006, temperatures in some of the passenger cars of the London Underground went as high as 47°C (116 °F). Signs at the stations advised passengers to carry a bottle of water to help keep cool. These were extreme temperatures, but it is still routine for passengers on some lines to suffer onerous heat even during a normal summer. How could this be in one of the world’s richest cities? Can’t they afford to air-condition the cars?

Money is not the issue. Conventional air conditioning has been ruled out on the deep lines because of the lack of space for equipment on trains and the further problem of dispersing the waste heat these would generate. Different solutions have been proposed to cool Underground trains, such as the use of great blocks of ice inside the cars. They would be kept in refrigeration units, to keep them from melting completely.

Gauge (in the railroad world) is the measure of track width. The London Tube system was designed in the nineteenth century with narrow tracks and matching tunnels that today, on the deep lines, cannot accommodate air-conditioning, because there is no room to ventilate the hot air from the trains. The standard gauge for the deep tunnels is narrow; these tunnels can have a diameter as little as 3.56 m (11 ft 8 in). The future, unforeseen result, was that tens of thousands of residents commuters would suffer a stifling commute every summer because the trains are locked into an inflexible design decision made more than a century before.

Lock in is not limited to the physical world. We all experience this with the limitations placed on our lives as a result of the choices we have made, or had forced on us, earlier in our lives—right back to our infancy. The environment, everywhere on earth, is under attack—-from global warming, to pollution of air, water and soil, to oil spills, radiation leaks, degrading landfills and on and on. But the Americans are off the hook on this: the primary responsibility for this lies with the 17th century French philosopher, René Déscartes.

Says philosopher Richard A. Watson:

“Déscartes is the architect of our modern world of individualistic, materialist science and technology….The modern world is Cartesian to the core because all science and technology is based on describing the material world mathematically as a vast machine whose various parts interact according to uniform laws of motion.”

Déscartes has cursed us, Watson goes on to say, “with the belief that what is important is not the subjective sensations and emotions we have within us but rather the objective things in the outer world that cause them….Emotions are subjective, trivial, useless and meaningless, and misleading. There are no emotions in the real world, so they should not be allowed to interfere with man’s serious, objective work of controlling nature.”

This was Déscartes ambition and goal: to make man “masters and possessors of nature.” This was also, of course, a biblical injunction (Gen. 1:28). Déscartes rejected all non-material aspects of the world, like mysticism and the occult, and envisioned the universe as a machine. Every action involving matter was purely mechanistic, and matter had no contact with spirit. To Déscartes, all animals—-including humans-—were mere machines. Humans had a spiritual aspect, a soul, but this had no link with our physical bodies.

René Déscartes is acknowledged as a good person but the Western world has become, inadvertently, an extension of his sterile personality. As science writer Jane Muir put it:

"Since Déscartes had shut emotion out of his life, it is little wonder that his philosophy does the same....As a rule, Déscartes was more a thinking machine than a man. Learning and knowledge were his passions; emotion had no place in his philosophy or his life….His work, rather than people, was his companion. He was an observer on the stage of life—not one of its actors."

Déscartes’ most important follower after his death in 1650 was Père Nicolas Malebranche, a man widely noted for his caring and compassion. Watson tells this story:

“While Père Malebranche and his friends were walking along, a pregnant dog came fawning up to them. Père Malebranche knelt down to fondle her. Then, making sure his friends had their eyes upon him, he stood up, pulled back his cassock, and kicked the poor animal in the stomach as hard as he could. The dog ran yelping down the street, and Père Malebranche’s companions exclaimed in horror. Then Père Malebranche hardened his voice, and this is the essence of what he said: Fie on ye! Restrain yourselves. That dog is nothing but a machine. Rub it there, it scratches. Whistle, it comes. Kick it, it yelps and runs away. There is a button to push and a mechanism for each of its actions. It is nothing but a machine. Save your compassion for human souls.”

Cartesian philosophy banished all non-rational truth to limbo; painting, music, poetry, literature—all were of no importance in Déscartes’ philosophy because he saw them as incapable of teaching us anything. Even the lessons of history are unimportant next to what can be learned by using the rational method. Reason, not experience, is what counts.

The mechanical universe was refined further by Isaac Newton as a clockwork initially set in motion by God. Newton, as a result of the psychic damage inflicted on him in his own childhood, carried on the scientific practice of denying feelings and emotions. He was apparently a virgin to the end of his life and, in contrast to Déscartes who Watson called “a real hard man”, Newton was what we would today call “a nasty piece of work”. In the following centuries, the idea of man being a machine and the universe being like a clock, totally took over the world of science. The Romantic poets of the 18th and 19th centuries, like William Wordsworth and Samuel Coleridge, opposed Isaac Newton who “explained” the rainbow and took wonder out of the world. They tried to create a new kind of poetry that emphasized intuition over reason and pastoral over urban, but they were voices in the wilderness of expanding industrialization. Such a movement (although no one reads much poetry anymore) could be more possible today. As medical essayist Lewis Thomas has written:

“We must rely on our scientists to help us find the way through the near distance, but for the longer stretch of the future we are dependent on the poets. We should learn to question them more closely, and listen more carefully. A poet is, after all, a sort of scientist, but engaged in a qualitative science in which nothing is measurable. He lives with data that cannot be numbered, and his experiments can only be done once.”

The clockwork universe ticked on. The object of the post-Cartesians was to transform man into the measurable and manipulable parts of the Great Machine. Johannes Kepler:

“My aim is to show that the celestial machine is to be likened not to a divine organism but rather to a clockwork.” Might it not be possible, he asked, “to show that the celestial machine is not so much a divine organism but rather a clockwork…inasmuch as all the variety of motions are carried out by means of a single very simple magnetic force of the body, just as in a clock all motions arise from a very simple weight.”

Galileo:

The world “is written in that great book which ever lies before our eyes—-I mean the universe-—but we cannot understand it if we do not first learn the language and grasp the symbols in which it is written. The book is written in the mathematical language, and the symbols are triangles, circles and other geometrical figures, without whose help it is impossible to comprehend a single word of it; without which one wanders in vain through a dark labyrinth.”

Philosopher Baruch Spinoza carried on where Déscartes had left off: “I shall consider human actions and desires in exactly the same manner as though I were concerned with lines, planes, and solids.”

Pierre Simon de Laplace:

A superhuman Intelligence “would embrace in the same formula the movements of the largest bodies in the universe and those of the lightest atom: nothing would be uncertain for it, and the future, like the past, would be present to its eyes.”

Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle:

“I esteem the universe all the more since I have known that it is like a watch. It is surprising that nature, admirable as it is, is based on such simple things.”

Julien Offray de la Mettrie:

“Let us conclude boldly then that man is a machine, and that there is only one substance, differently modified, in the whole world. What will all the weak reeds of divinity, metaphysic, and nonsense of the schools, avail against this firm and solid oak.”

By the nineteenth century, T. H. Huxley argued that “all vital action may…be said to be the result of the molecular forces of the protoplasm which displays it.” In a lecture, he said that

“the thoughts to which I am now giving utterance and your thoughts regarding them, are the expression of molecular changes in that matter of life which is the source of our other vital phenomena.”

To Huxley, the progress of science meant “the extension of the province of what we call matter and causation, and concomitant banishment from all regions of human thought of what we call spirit and spontaneity.”

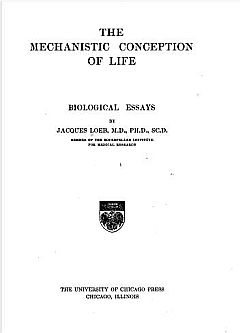

In 1912 biologist Jacques Loeb published The Mechanistic Conception of Life in which he claimed that organisms are machines. In the same year, Edwin Tenney Brewster publishedNatural Wonders Every Child Should Know:

“For of course the body is a machine. It is a vastly complex machine, many, many times more complicated than any machine ever made with hands; but still after all a machine. It has been likened to a steam engine. But that was before we knew as much about the way it works as we know now. It really is a gas engine; like the engine of an automobile, a motor boat or a flying machine.”

Staying with the machine metaphor, science writer Isaac Asimov in the 1990s denied the incredible mysteries of quantum physics, saying that the uncertainty principle of quantum physics

“fuzzed everything out into probability,” although “this didn’t mean that the universe was not a machine. It simply meant that we didn’t know as much about machines as we thought we did,” concluding that, “I’m a twentieth-century mechanist—and a very thoroughgoing one—and I will not admit that there is any reason to suppose that everything in the universe cannot be satisfactorily explained on the basis of material things (with energy and matter both considered material).”

By the 1950s human minds were likened to computers as in Jacob Bronowksi:

“The electronic machines are remarkable for their speed and therefore for the amount of work they can do in a manageable time. They do this not by their complexity but by their simplicity. Like the human brain, they achieve complexity only by the repetition of simple elements—tubes or circuits, where the brain repeats the same unit cells.”

This is a reverse metaphor where he is saying that computer elements are “like the human brain”. Four decades later, the simile became more sophisticated, as in Harvard evolutionary psychologist Steven Pinker:

“The mind is a neural computer, fitted by natural selection with combinatorial algorithms for causal and probabilistic reasoning about plants, animals, objects, and people. It is driven by goal states that served biological fitness in ancestral environments, such as food, sex, safety, parenthood, friendship, status, and knowledge.” (emphasis added)

MIT Artificial Intelligence scientist Marvin Minsky goes on to say: “ The brain is hundreds of computers that evolved for five hundred million years .”

There are some, like biologist Richard Dawkins, who apparently don’t understand that metaphors are only metaphors when he says “The machine code of the genes is uncannily computerlike…”

The Cartesian philosophy has carried on unchanged in our society today. As Dawkins writes:

“[T]he welfare state is a very unnatural thing….There is no need for altruistic restraint in the birth-rate, because there is no welfare state in nature….Since we humans do not want to return to the old selfish ways where we let the children of too-large families starve to death, we have abolished the family as a unit of economic self-sufficiency, and substituted the state. But the privilege of guaranteed support for children should not be abused.”

The most influential psychologist of the twentieth century was the Harvard behaviouralist B. F. Skinner:

“To man qua man we readily say good riddance. Only by dispossessing him can we turn to the real causes of human behavior. Only then can we turn from the inferred to the observed, from the miraculous to the natural, from the inaccessible to the manipulable.”

Stephen Pinker:

“Thoughts and thinking are no longer ghostly enigmas but mechanical processes that can be examined and debated. I find it particularly illuminating to see the shortcomings of the venerable doctrine of the association of ideas, because they highlight the precision, subtlety, complexity, and open-endedness of our everyday thinking. The computational power of human thought has real consequences. It is put to good use in our capacity for love, justice, creativity, literature, music, kinship, law, science and other activities...”

The image, taken by the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) aboard |

Marvin Minsky could be channelling the long-dead Déscartes:

“The brain is hundreds of computers that evolved for five hundred million years. It’s a wonderful natural phenomenon, and we have to understand how this thing works. We must sweep aside the idea that the mind is animated by a soul or a spirit or anything like that. In fact, my view is that there is something insulting and degrading about the idea of a soul, and the idea of a spirit.” (emphasis added)

Despite the fact that the Hubble Space Telescope can see billions of light years into spsace, science has actually shrunk man’s world. As essayist J. B. Priestly noted:

“It is our Life-shrinkers who have been busy as long as I can remember just sealing us down and then squeezing the juice out of us. We quit their company feeling like desiccated dwarfs. The most important of them have been lop-sided ‘nothing but’ men on the very highest and most imposing level. And to prove I am not dealing in vague abuse, I will stick my neck out as far as it can go. Among the very greatest names of the last hundred years, those men whose influence can hardly be over-estimated, are Marx, Darwin and Freud. And with all due respect for their personal qualities, I say that all three of them, working in their very different fields, have been Life-shrinkers.”

Science, as currently practiced and promoted, has no juice. Just as Déscartes divorced the mind from the body, so science has separated man from the universe at large. The result, says physicist Roger Jones, is that "in place of a nurturing, participatory universe, we are supposed to soothe and pacify ourselves with a detachment and objectivity toward our environment which can only be considered pathological ."

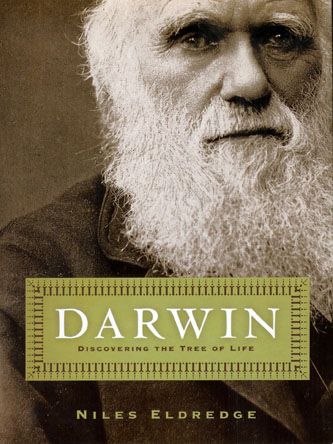

Even Charles Darwin discovered, too late, that science had shrivelled his soul. In 1869 (he was only 60 and lived 13 more years) he said that he would very much like to hear Handel’s Messiah again, but was afraid to try it. “I dare say I should find my soul too dried up to appreciate it as in old days; and then I should feel very flat.”

He felt he was “a withered leaf for every subject except Science” and added: “It sometimes makes me hate Science, though God knows I ought to be thankful for such a perennial interest.” His unhappiness over the loss of former pleasures increased over the years. In his Autobiography he pondered his “curious and lamentable loss of the higher aesthetic tastes”; and found that he “could not endure to read a line of poetry”, and that his mind had become “a kind of machine for grinding out general laws out of large collections of facts.”

He went on to conclude: “If I had to live my life again, I would have made a rule to read some poetry and listen to some music at least once every week.” If he had done that, he said, “Perhaps the parts of my brain now atrophied could thus have been kept active through use.” Reflecting the Romantic poet Wordsworth’s view of the value of imaginative writing for sympathy and moral understanding, he explained that the loss of the taste for poetry was “a loss of happiness, and may possibly be injurious to the intellect and more probably to the moral character, by enfeebling the emotional part of our nature.”

Darwin’s lesson remained unlearned by scientists who followed him and society as a whole as the spiritual aspect of society has not only become “enfeebled”, but aggressively denied. Ultra-Darwinist biologist Richard Dawkins (The God Delusion) tries to give desiccated science a patina of humanity:

“I believe that an orderly universe, one indifferent to human preoccupations, in which everything has an explanation even if we still have a long way to go before we find it, is a more beautiful, more wonderful place than a universe tricked out with capricious, ad hoc magic.”

Science is essentially about nihilism and while there are those who blame science for many of the world’s ills, I suggest that it is not science per se that is the culprit, but rather the cultural philosophy that comes from science. As biologist Stuart Kauffman writes: “Science has left us as unaccountably improbable accidents against the cold, immense backdrop of space and time.” As a direct, demonstrable result of Cartesianism, mankind has, over the last three or four centuries fouled his own nest—the earthly environment he needs to live and grow. As philosopher Theodore Roszak puts it:

“Rape begins by denying the victim her dignity, autonomy, and feeling. Psychologists now call this ‘objectifying’ the victim. When it is another human being who is being so objectified, everybody (except perhaps the rapist) can clearly see that it is a crime. But when we objectify the natural world, turning it into a dead or stupid thing, we have another word for that. Science.”

He goes on:

“In four centuries of taking wealth and comfort from the body of the Earth, modern science has not troubled to produce a single rite or ritual, not even a minor prayer, that asks pardon or gives thanks. But then what sense would it make to ask anything of a dead body?”

Western society has been living in thrall to a Cartesian paradigm or worldview. It was the humanist psychologist Abraham Maslow who said: “It is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail”. An alien concept to science, this has nevertheless become a bit of folk wisdom and a truism. The hammer in our society is the paradigm of materialistic science. But as Roger Jones points out "Science is no longer a field of study—an 'academic' discipline. In our culture, it has become a way of life and a system of belief. At its worst, science is a form of idolatry."

This is where the rubber meets the road.

Our culture is a Cartesian paradigm that was intentionally chosen centuries ago and no one recognizes that we could have chosen a different paradigm. Contrary to René Déscartes there are other, legitimate ways, of looking at the world. They just contrast and conflict with the materialism of science and are thus dismissed out of hand. This is not a matter of discarding science or throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Around the time that Déscartes was born, Shakespeare wrote his play Hamlet, who, in the play, after seeing the ghost of his father declares: “There are more things on heaven and earth Horatio than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

This is not an idea that has gained any traction within Cartesianism. Dawkins writes: “Ordinary superstitious folks…are the ones who love a good ghost story…[and] never lose an opportunity to quote Hamlet… and the scientist’s response (“Yes, but we’re working on it) strikes no chord with them.”

The Cartesian paradigm is maintained through language that is so pervasive that we don’t even notice how it has distorted our thinking about the world. Government, for example, tries to conserve and protect the environment through a variety of laws and regulations, but there is resistance. For all its toothlessness and impotence, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is often called a “job-killer”. In our society jobs are important for far more than just supplying an income so people can meet the basic physical needs of themselves and their families. Jobs are needed so people can consume which has created a vicious cycle of work/consume/work that has destroyed any connection people have with the world beyond materialism. As Vance Packard wrote in his 1960 book, The Wastemakers:

“The people of the United States are in a sense becoming a nation on a tiger. They must learn to consume more and more or, they are warned, their magnificent economic machine may turn and devour them. They must be induced to step up their individual consumption higher and higher, whether they have any pressing need for the goods or not. Their ever-expanding economy demands it.”

How society’s Cartesian paradigm works and is maintained is the subject of the next article.

============================================

Daniel Johnson was born near the midpoint of the twentieth century in Calgary, Alberta. In his teens he knew he was going to be a writer, which is why he was one of only a handful of boys in his high school typing class — a skill he knew was going to be necessary. He defines himself as a social reformer, not a left winger, the latter being an ideological label which, he says, is why he is not an ideologue. From 1975 to 1981 he was reporter, photographer, then editor of the weekly Airdrie Echo. For more than ten years after that he worked with Peter C. Newman, Canada’s top business writer (notably on a series of books, The Canadian Establishment). Through this period Daniel also did some national radio and TV broadcasting. He gave up journalism in the early 1980s because he had no interest in being a hack writer for the mainstream media and became a software developer and programmer. He retired from computers last year and is now back to doing what he loves — writing and trying to make the world a better place

Daniel Johnson was born near the midpoint of the twentieth century in Calgary, Alberta. In his teens he knew he was going to be a writer, which is why he was one of only a handful of boys in his high school typing class — a skill he knew was going to be necessary. He defines himself as a social reformer, not a left winger, the latter being an ideological label which, he says, is why he is not an ideologue. From 1975 to 1981 he was reporter, photographer, then editor of the weekly Airdrie Echo. For more than ten years after that he worked with Peter C. Newman, Canada’s top business writer (notably on a series of books, The Canadian Establishment). Through this period Daniel also did some national radio and TV broadcasting. He gave up journalism in the early 1980s because he had no interest in being a hack writer for the mainstream media and became a software developer and programmer. He retired from computers last year and is now back to doing what he loves — writing and trying to make the world a better place

Salem-News.com:

googlec507860f6901db00.html

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

Connor_Sanchez September 27, 2020 7:47 am (Pacific time)

School of Environmental Forest Sciences, College of the Environment, University of Washington, Box 352100, Seattle, WA 98195-2100, USA. stasah@uw.edu Diagnostic reframing of intractable environmental problems: case of a contested multiparty public land-use conflict

Natalie September 3, 2010 11:45 pm (Pacific time)

Careful choice... yes, but it's also a very odd choice considering the "full ID of writer". I've never seen a portrait of Darwin looking so miserable and depressed; always an undefeatable hero type.

Vic September 4, 2010 8:11 am (Pacific time)

"Isolate", I do not think that a shortage of resources is America's problem, it is where those resources are going. The bottom 80% of Americans hold only 7% of the nation's wealth. The United States could produce enough food to feed the world five times over, according to a Hunger Project study in 1980. America is being looted by the military/industrial/security axis of evil, and it seems that there is no longer even much effort expended to hide this fact.

Natalie September 3, 2010 8:02 pm (Pacific time)

Careful choice...yes, but it's also a very odd choice, considering "full ID of writer". I should, probably, e-mail this image to my former mid school. I doubt they ever searched for a pic of such miserably looking Darwin.

Hank Ruark September 2, 2010 9:53 am (Pacific time)

Natalie et al: It is natural manipulative protocol to pick the picture to parallel and potent-ize what the writer intends to be the image of those about whom he writes. That's part of propaganda techniques seen every day, on tv and in every form of print. If you don't have one with the negative-impact built-in, these days simple Google-ized image manipulation can provide precisely the look one seeks --even to squint and scowl !! Of course, for most where such images are presented, we know from full ID of writer that no such action would ever be taken -- don't we ?? Not necessarily manipulation, but careful choice...

Isolate? August 31, 2010 2:59 pm (Pacific time)

In graduate school I spent several years wrestling with the texts of the atheistic philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who taught me one unforgettable lesson: Those who lack the tragic sense of life are apt to invent realities to replace the one they cannot face. Nietzsche aimed his argument at Christianity, with its supposed invention of an otherworldly paradise. He was wrong on this score, however: The Christian faith affirms the inevitability of suffering. The cross is a perennial reminder of the tragic limitations that all human beings must not only bear but choose. Some of my associates believe that nature loses its moral power when God is removed from the picture, and the natural and social sciences replace theology as the highest source of intellectual authority. Believing that scientists speak the truth on all subjects, legislators and administrators tend to accept their pronouncements, even on moral matters outside their purview. I wonder where Al Gore and all the other proponents of man-caused global warming fit? God only knows they have no evidence that warming or the cooling going on is man-caused. Those who accept life's tragic limitations, however, view existence as a gift -- something they may not and should not try to manipulate. They accept that there are moral limits on what the human will and can accomplish in the face of death. a country renowned for its optimism, we Americans go too far when we assume that sorrow and suffering can be avoided, and that, by manipulating life, we can beat death. Maybe the time has come to reduce, or maybe just cut off all assistance to those in need outside of our borders until all our citizen's needs have been met. Our resources grow short, so I say isolate those resources for Americans only, like what most of the rest of the world does.

Hank Ruark August 30, 2010 2:42 pm (Pacific time)

Friend Dan: What a loathsome hole-istic world you have dug up here !! Can hardly wait for next parts to see how you will fill it in...and with/what. Do very honestly appreciate your "awesome" talent (Tim, note !) and look forward to learning still more from your stuff...as I always have from your arrival onwards. Honest Injun, if you'll pardon the reference !!

Natalie August 30, 2010 12:38 am (Pacific time)

What happened to Darwin? No offense, but he has an expression of a very sad orangutan...as if they made him listen to Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata for a week without breaks. No wonder he decided to break out.

As I said in my article, Natalie, his life was shrunk; he realized it, but it was too late. No wonder he looks sad. He was.

He was also an atheist and his wife a devout Christian. Her big concern was that after she died, she would not be able to spend eternity with him. He was not without feelings. When his wife Emma was pregnant with her first child and realized that she might die in childbirth, not uncommon at the time, she wrote him a note which he kept for the rest of his life. He wrote to her, on the outer fold: “When I am dead, know that many times I have kissed and cried over this.”

[Return to Top]©2026 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.